Here's a draft of some sketchy thoughts that I'm putting together for a project being put together by those fine folks at EIPCP.

1. “One publishes to find comrades!” (1997: 52) This declaration

by Andre Breton is a fitting place as any to begin discussing what an

insurrection of the published means, or could mean. For what Breton says here

is not a facile declaration, but really something that is worth reflecting on

to consider changes in the current and shifting relation relationship between

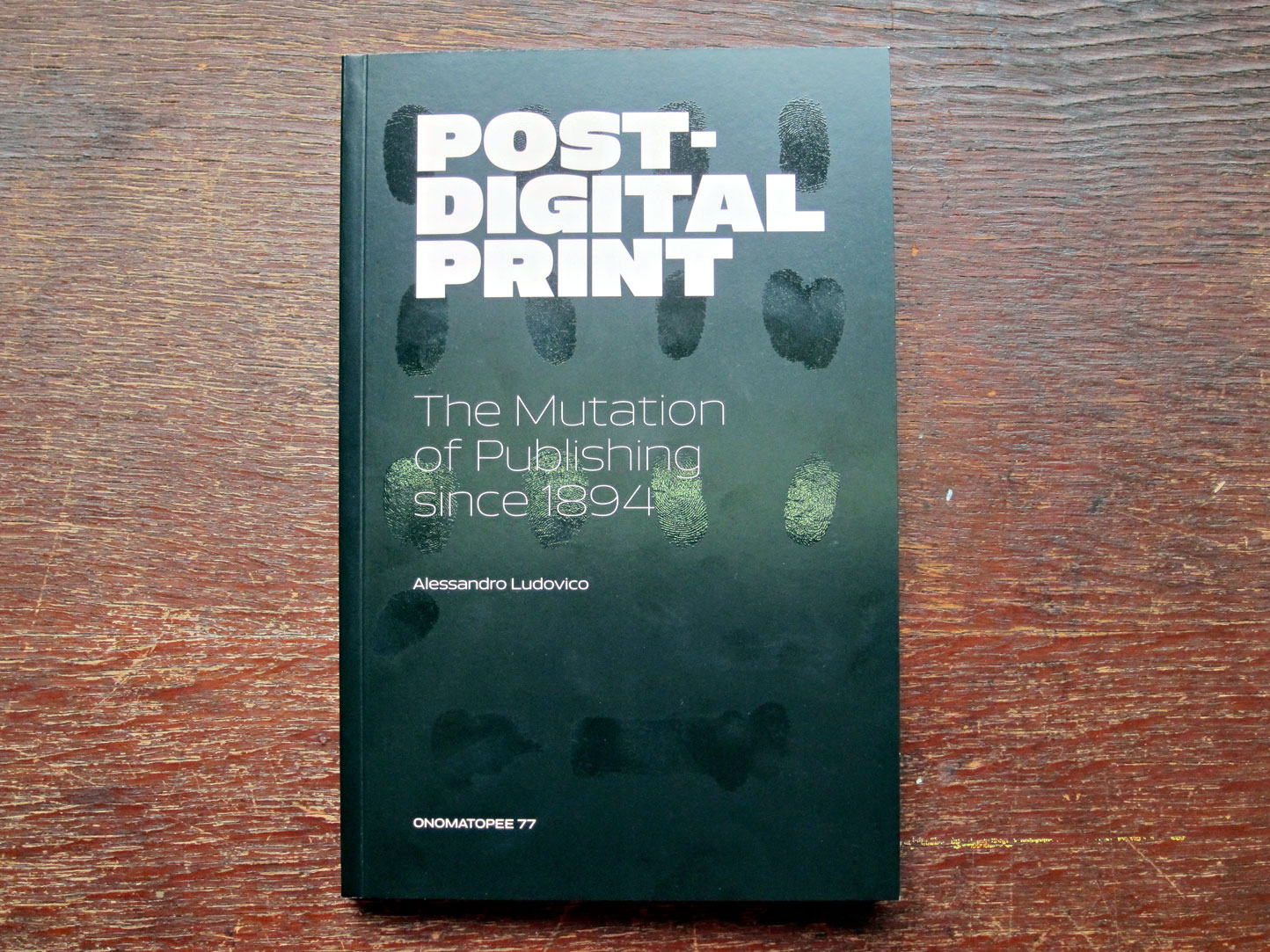

publishing, politics, and cultural labor more generally. For what Breton says

here is not that one publishes to

propagate and spread an already conceived an absolute: this is not a publishing

of revelation or of bringing consciousness to an already imagined fixed

audience. Rather Breton is describing something that might be called a

publishing of resonance. That is, not a publishing practice that is intent on

necessarily intent on trying to convince anyone of anything, but rather is

working towards establishing conditions for the co-production of meaning. Thus

publishing is not something that occurs at the end of a process of thought, a

bringing forth of artistic and intellectual labor, but rather establishes a

social process where this may further develop and unfold.

2. In this sense the organization of the

productive process of publishing could itself be thought to be as important as

what is produced. How is that? It follows logically from the idea that one

publishes in order to animate new forms of social relationships, which are made

possible through the extension and development of publishing, through the

social relationships animated by it. Publishing calls forth into itself, and

through itself, certain skills of social cooperation that are valuable and

worthy, even if what is produced as an end product perhaps is not an exalted

outcome. Perhaps that is not so important at all. In short publishing is the

initiation of a process where embodied processes of knowing and understanding

are produced and reproduced, rather then the creation of fixed objects where

complete understanding are fixed and contained. The production of the community

of shared meaning and collaboration, the production of a public, contains

within it a wealth that is often greater then a single text. The production of

the text can only be valuable because of the social relationships it is

embedded with and produces meaning through.

3. It is for this reason that historically there

has been a close relationship between forms of social movements and changes in

media production. This can be seen clearly in Sean Stewart’s excellent book On the Ground, which explores the

connection between the development of the underground and counterculture scene

and the emergence of alternative publishing in the 1960s (2011). There is a

similar relationship that has been often explored in the development of radical

politics in the 1970s, particularly around punk, and the rise of ‘zine

production, and the use of photocopiers (2008). Likewise Jodi Dean has likewise

suggested that there was a great importance played in the formation of the

Bolshevik party by the necessities imposed by the running of a daily newspaper,

with the intense commitments and forms of organization necessary to sustain

that (2012). This is not to fall into a McLuhan-esque technological determinism

where shifts in media form map directly on to and determine changes in social

composition. Rather is to acknowledge that media production and social movement

cultures are closely intertwined, such as that shifts between them are

complicated and multilayered.

4. One could likely come up with a great number of

further examples to think about the relationship between shifts in print and

politics, conducting a comparative analysis of them, and what differences these

shifts have meant for those involved in them. And that would be useful, perhaps

leading to developing a more refined grammar of political subjectiviation in

relationship with the changing nature of print-politics.[i]

And this could be followed by the explosion of enthusiasm that came with the

various waves and changes in the rise of net technology, which managed to

return after repeated bursting of various tech bubbles, to rise again with each

new and successive form of technological interaction, from blogging to social

media (Henwood 2003). But as important as these lessons would be, to discuss an

insurrection of the published would mean to return to these previous moments to

learn from them to addressing the dynamics of the present. What are the current

conditions of print-politics as affects by changing regimes of labor, culture, and

media?

5. One might be tempted to think about the current

dynamics of print-publishing starting from David Batterham’s clever throw away

line that most booksellers are quite odd, which he suggests is not all that

surprising “since we have all managed to escape or avoid more regular forms of

work” (2011: 7). The problem with that observation is that while once it may

have been possible to escape from ‘more regular forms of work’ work through

certain forms of literary and publishing pursuits, today it much more seems

that it is worked which escaped from us, in the sense that there the number of

decent paying jobs left within publishing and media industries more generally.

The other day I was discussing with a friend working for a fairly large

independent press who described the way that he was nearing forty years old,

was working in something close to what he would imagine as his dream job, but

still needed to share a house with three other people and subsist on an income

more fitting of a student existence then someone who has worked in a

professional job for over ten years. One might be tempted to describe this,

much as Jaron Lanier does (2013) as part of the generalized gutting of middle

class jobs, particularly in forms of cultural work and media production,

brought about by the effects of network technologies and labor.

6. Are we then experiencing a death of print?

Alessandro Ludovico has recently written an excellent book tracing out the

history of this suggestion from its first recorded instance in 1894 to the

present (2012). Perhaps not surprisingly, given that it is now possible to

trace out more then a century of the idea, print’s proclaimed impending death

seems a bit overstated, repeatedly. But that print seems unlikely to die does

not mean that it is not changing, being drastically affected by constant shifts

in technology and the dynamics of the digital world. Print publishing finds

itself transformed by conflicting demands and roles, embedded into shifting expectations

about the roles of various media, and familiarity with engaging with multiple

media platforms. Ludovico suggests that these mutations in the politics and

publishing could paradoxically lead to a revitalization of print. Personally I

would very much welcome this development, as despite the explosion of materials

available created by digital media, there is a certain hapticality that gets

lots along the way. This revitalization of print would more then likely not be

as the same mass medium that it was before. It is perhaps parallel to way that

the rise of digital medias in music has been accompanied by the return of vinyl

as a medium celebrated for its aesthetic qualities.

7. It is in this conjunction of social and

technological dynamics that I would situate a project like Minor Compositions,

which is the imprint series that I have been editing and running for

Autonomedia since 2009. Its overall approach and orientation is closely aligned

with the history of Autonomedia itself, which has been printing works of

anarchist and autonomist political theory, culture, and history since the early

1980s. Minor Compositions started as a subproject of Autonomedia, in the sense

that it was (and is) part of it, but operating with a high degree of editorial independence.

And while Autonomedia has always been quite skeptical around claims of

intellectual property and the enclosures of knowledge by copyright, this has

usually meant that we were comfortable with other people taking up and

distributing freely work that we had done. And in a number of cases this is

precisely what happened, leading to a much wider and developed forms of

distribution then would have otherwise occurred, such as the widespread dissemination

of Hakim Bey / Peter Lamborn Wilson’s writing. For the most part it did not

mean the free posting of finished book files on the net. This is a step that

Minor Compositions took further, posting the finished PDF of every title

produced for free download. This has been the case for each and every one of

the nineteen titles that have been produced thus far. Although it cannot be

said that there has been a purely positive relationship between the free

sharing of information and the ability of the project to reproduce itself – it

is a much more complex one where this open sharing has incurred significant

costs, as well as produced benefits in terms of circulating and developing

ideas.

8. The question still remains, where does this leave the politics

of open source publishing? Can we say that there still is a politics to open

publishing at a point where it has become, even if a somewhat distorted and

watered down form, the stated policy of numerous governments? I would argue

that yes, there still are political potentialities found within open

publishing, within and for an insurrection of the published, but they are both

murkier and complicated then there were previously. Where several years ago it

might have seemed reasonable to think that the very act of publishing openly

could provide the basis of a politics, that this provided a counter to the

argument of conservatives like Mark Helprin who levied accusations of those

involved in open source cultural production as being the harbingers of a new

digital barbarism (2009), this today is no longer the case. The act and process

of open source publishing is not in itself sufficient as the basis of a

politics. Rather it is a question, going back to Breton, of what is made

possible through the process of open publishing. And this is the argument made

by Gary Hall, one of the founders of Open Humanities Press, who argued that “the ethics and politics of open-access publishing

and archiving do not simply come prepackaged, but have to be creatively

produced and invented by their users in the process of actually using them” (2008:

27).

9. What this means that is the constant recourse to or invocation

of the notion of openness might indeed be a precondition of the insurrection of

the published, but it is not its only characteristic. Rather we end up with

questions how, what, and form whom is this openness constituted? Or perhaps

more fundamentally, what is the open is open publishing? What kinds of social

relationships does it support? What kinds does it work to prevent? How can it

serve to further the sociality in publishing argued for by someone like Breton?

One interesting way to think through these kinds of questions, even if a bit

strange, would be to return to Agamben’s commentary on Jakob Johann von

Uexküll’s research about ticks (2004). As Uexküll describes the tick is it

completely open the world. But in saying that its openness is constituted in a

rather limited fashion: namely sensing the movement of warm blooded mammals

below it so that it can drop itself on to them, suck out its necessary

nourishment, and then die. In this version of the open it is not an unlimited

capacity for becoming and transformation, but rather the organisms capacity to

interact with its particular world. Thus it is not true to say the tick is not

open the world; it is as open as can be, and sustains itself through that

relationship to the world.

10. The insurrection of the published must start

from these questions: what is the openness to the world produced through the

social relationships of publishing we currently find ourselves in? This is not

a question that can be answered by looking at the politics of media production

just by themselves, or the labor involved in the production of media, no matter

how directly political or not they might appear to be. Rather it is a question

of media ecologies, where print politics are embedded within larger ecologies

of media production, circulation, distribution, and consumption – and at a time

when the difference between these previously distinct actions have tended

increasingly to blur into one another. It is not just a question of the best

way to organize autonomous print and media production, although that is an

important ask, but also the best ways to organize the publics and undercommons

that are articulated through autonomous media production, and which feedback

through and support continuing development and lifeworld of autonomous media

production. Like Breton would still say today, one publishes in order to find

comrades, but not merely to find comrades as the consumers of information or

media, but rather as co-conspirators and accomplices.

References

Agamben, Giorgio (2004) The Open. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Batterham, David (2011) Among Booksellers: Tales Told in Letters to Howard Hodgkin. York:

Stone Trough Books.

Breton, Andre (1997) quoted in Gareth Branwyn Jamming the Media: A Citizen’s Guide Reclaiming the Tools of

Communication. Vancouver: Chronicle Books.

Dean, Jodi (2012) The Communist Horizon. London: Verso.

Duncombe, Stephen (2008) Notes

from the Underground. Bloomington: Microcosm.

Hall, Gary (2008) Digitize This Book! The Politics of New Media, or Why We Need Open

Access Now. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Helprin, Mark (2009) Digital Barbarism: A Writer’s Manifesto. New York: Harper.

Henwood, Doug (2003) After the New Economy. New York: New Press.

Lanier, Jaron (2013) Who Owns the

Future? London: Penguin.

Ludovico, Alessandro (2012) Post-Digital Print – The Mutation of Publishing since 1894.

Eindhoven: Creating 010.

Stewart, Sean (2011) On the Ground. Oakland: PM Press.

Negt, Oskar and Alexander Kluge (1988) “The Public Sphere and Experience:

Selections,” October Vol. 46: 60-82.

[i] There

is an immense amount of scholarship across multiple fields that has explored

precisely these questions, from the work of Habermas on the rise of the public

sphere, through Negt and Kluge’s notion of the proletarian public sphere

(1988), to Michael Warner and Nancy Fraser’s updating and expanding of public

sphere theory.